The Hezeta and Bodega Expedition of 1775: First Contact on the North Coast

On display in our Community Case

October 21- November 24

October 21- November 24

For thousands of years the peoples of Oceania had been migrating and colonizing the vast expanse of islands of the world's largest ocean. In the Age of Discovery, trade empires followed the prevailing winds searching the Western Hemisphere for routes linking the riches of Asia to Europe, yet up until the 18th century, the coasts and continents of the Pacific Ocean were still largely unknown to the great maritime nations of the day. With a renewed impetus for exploration spurred on by colonial rivalries and a quest for knowledge inspired by the Enlightenment, interests arose that drove further investigation into geography, natural science and ethnography.

As early as 1728, Danish-born navigator Vitus Bering and Russian navigator Aleksei Chirikov, sailing for Imperial Russia, lead several expeditions, mapping portions of northeastern Siberia and what is now the Gulf of Alaska. In 1768, English explorer James Cook headed a to the southern Pacific to map the coasts of New Zealand and Australia before circumnavigating the globe. Spain entered the race in 1774 when Juan Pérez, veteran navigator of the California coast, set sail aboard the frigate Santiago from the naval base at San Blas on the west coast of Mexico to explore the northwest coast of North America. His instructions, given by Viceroy Bucareli of New Spain, were to ascend northward to a latitude of 60° and reconnoiter the coast to Monterey in California as he returned south. Along the way, he would search for signs of foreign intrusion (most likely Russian or English), observe the indigenous tribes, and chart the coast. Moreover, Pérez was also charged with going ashore where possible and making a formal claim for Spain. The commander was explicitly cautioned that he was not to take anything from the native people against their will, but rather, interact with friendship and kindness and “under no circumstances should he antagonize the Indians or forcibly take possession of land.” Furthermore, they were not to engage any foreign ships or settlements that they might encounter nor reveal the nature of their mission. The Santiago approached the islands of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) off the west coast of today's British Columbia where, for the first time, the crew met and traded with the Haida people who sailed out in canoes to greet the ship. Sailing further north, he attempted to enter the Dixon Channel at latitude 54°40' before turning south to be the first nonnative to see Vancouver Island. However, at no point on this arduous journey was he or his ship's company able to land.

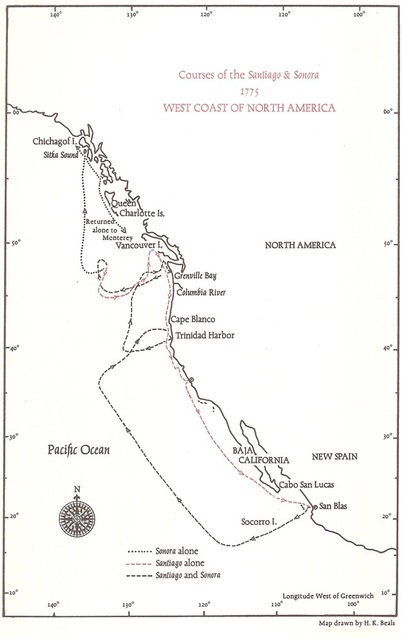

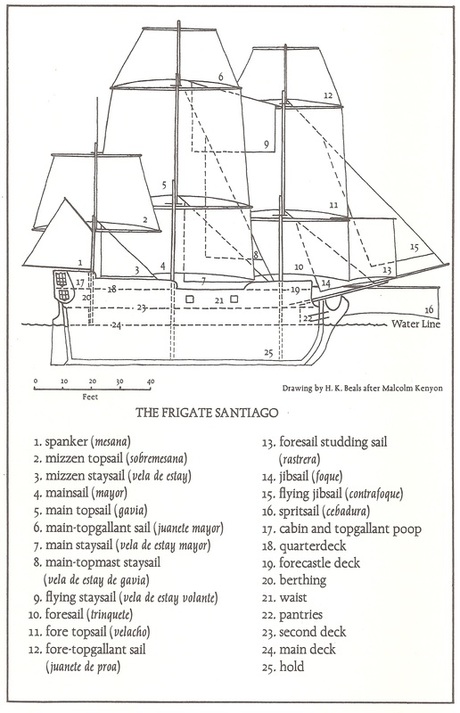

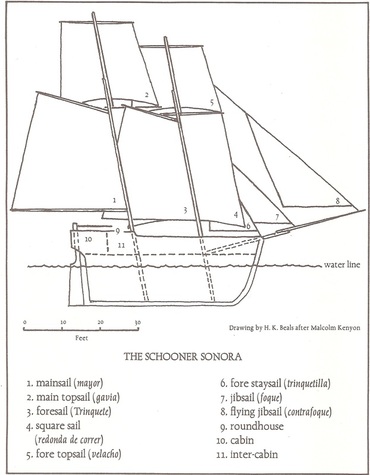

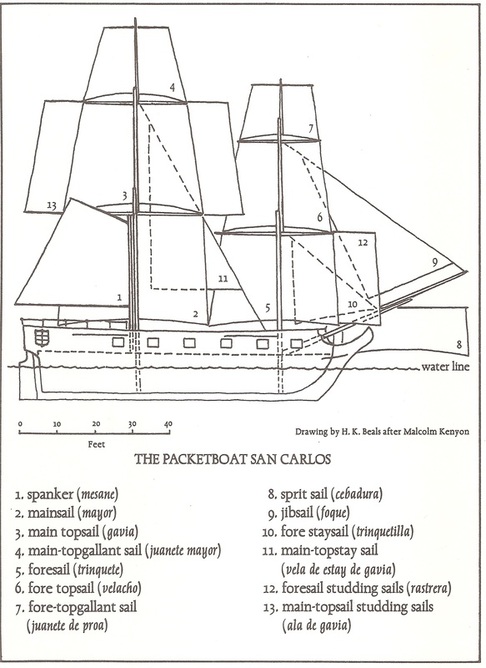

Charles III, keen to the strategic importance of the Pacific Northwest to the security of New Spain and the intelligence that such exploration could provide, had already ordered the appointment of six officers to San Blas and in 1775 a second expedition was launched. On March 16, just weeks before rebellion erupted in the British colonies on the East Coast, two ships, the frigate Santiago and the schooner Sonora, under the command of Bruno de Hezeta, left port with instructions to proceed to 65° latitude and survey the coast. A third ship also left that day, the packet boat San Carlos, bound for Monterey with a cargo of supplies would, under the command of Juan Manuel de Ayala, proceed north to San Francisco Bay, becoming the first expedition to enter and explore that harbor.

As early as 1728, Danish-born navigator Vitus Bering and Russian navigator Aleksei Chirikov, sailing for Imperial Russia, lead several expeditions, mapping portions of northeastern Siberia and what is now the Gulf of Alaska. In 1768, English explorer James Cook headed a to the southern Pacific to map the coasts of New Zealand and Australia before circumnavigating the globe. Spain entered the race in 1774 when Juan Pérez, veteran navigator of the California coast, set sail aboard the frigate Santiago from the naval base at San Blas on the west coast of Mexico to explore the northwest coast of North America. His instructions, given by Viceroy Bucareli of New Spain, were to ascend northward to a latitude of 60° and reconnoiter the coast to Monterey in California as he returned south. Along the way, he would search for signs of foreign intrusion (most likely Russian or English), observe the indigenous tribes, and chart the coast. Moreover, Pérez was also charged with going ashore where possible and making a formal claim for Spain. The commander was explicitly cautioned that he was not to take anything from the native people against their will, but rather, interact with friendship and kindness and “under no circumstances should he antagonize the Indians or forcibly take possession of land.” Furthermore, they were not to engage any foreign ships or settlements that they might encounter nor reveal the nature of their mission. The Santiago approached the islands of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) off the west coast of today's British Columbia where, for the first time, the crew met and traded with the Haida people who sailed out in canoes to greet the ship. Sailing further north, he attempted to enter the Dixon Channel at latitude 54°40' before turning south to be the first nonnative to see Vancouver Island. However, at no point on this arduous journey was he or his ship's company able to land.

Charles III, keen to the strategic importance of the Pacific Northwest to the security of New Spain and the intelligence that such exploration could provide, had already ordered the appointment of six officers to San Blas and in 1775 a second expedition was launched. On March 16, just weeks before rebellion erupted in the British colonies on the East Coast, two ships, the frigate Santiago and the schooner Sonora, under the command of Bruno de Hezeta, left port with instructions to proceed to 65° latitude and survey the coast. A third ship also left that day, the packet boat San Carlos, bound for Monterey with a cargo of supplies would, under the command of Juan Manuel de Ayala, proceed north to San Francisco Bay, becoming the first expedition to enter and explore that harbor.

Sailing a course into the open ocean of the Pacific and northward, the voyage of the Santiago and the Sonora looped eastward, approaching the shore around what is now Point St. George, and sailing southward, began searching the coast for a safe anchorage. The tiny escort Sonora, commanded by Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, was instrumental in locating a small harbor as it sailed ahead of the flagship, navigating the rocky coastline. As the two ships rounded a prominence that promised shelter, they were approached by several Indian canoes whose occupants were welcomed aboard each ship and, with no misgivings, they traded skins for knives and beads with the crew. Upon entering the port, the voyagers sighted a small rancheria at the edge of a mountain near the shore. They had arrived at Tsurai village in the land of the Yurok on June 9th, 1775.

The following day, the two captains and their contingent went ashore to call on the natives. The Indians, suspicious at first of the strangers in their midst soon relaxed their weapons, accepted gifts, and mingled with the crew until evening. On June 11th, the expedition proceeded to the top of the mountain sheltering the bay (Trinidad Head) and there they performed a formal possession ceremony, erecting a wooden cross and celebrating Mass as the Indians were content to look on from the rancheria. Being the feast day of the Holy Trinity, the port was named La Santísima Trinidad.

In the following days, the crew reprovisioned the ships with ballast, wood, and water, being assisted in their chores by the Indians who volunteered their help. Top masts were cut and fashioned and the schooner was boot-topped to clean its hull. The sailors interacted quite convivially with the native community, visiting them in their homes, and when a meal was taken ashore by the crew they were joined by families from the rancheria. According to one of the Santiago's chaplains, Fray Miguel de la Campa Cos, the sailors evidently heeded the commander's prudent orders to be on their best behavior.

The members of the expedition described the Indians they met as affable and it was likely that the villagers viewed the wayfarers as potential trading partners and possible allies against their traditional enemies. However, the genuine hospitality of their village hosts was made abundantly apparent when two of Santiago's apprentice seamen went missing. One of them, Pedro Lorenzo, having returned to his ship, implicated the natives in his disappearance and that of his shipmate Joseph Antonio Rodriguez. Amicable relations could have taken a turn for the worse when Hezeta, much to the disapproval of his fellow officers, conducted his search through the village for the second seaman in a hot-headed rampage. When the truth was found that the Indians had nothing to do with the desertion of Rodriguez, Lorenzo was punished for his inveracity, but in an expression of compassion, the Tsurai residents intervened on his behalf, imploring the commander to spare him the scourging.

The following day, the two captains and their contingent went ashore to call on the natives. The Indians, suspicious at first of the strangers in their midst soon relaxed their weapons, accepted gifts, and mingled with the crew until evening. On June 11th, the expedition proceeded to the top of the mountain sheltering the bay (Trinidad Head) and there they performed a formal possession ceremony, erecting a wooden cross and celebrating Mass as the Indians were content to look on from the rancheria. Being the feast day of the Holy Trinity, the port was named La Santísima Trinidad.

In the following days, the crew reprovisioned the ships with ballast, wood, and water, being assisted in their chores by the Indians who volunteered their help. Top masts were cut and fashioned and the schooner was boot-topped to clean its hull. The sailors interacted quite convivially with the native community, visiting them in their homes, and when a meal was taken ashore by the crew they were joined by families from the rancheria. According to one of the Santiago's chaplains, Fray Miguel de la Campa Cos, the sailors evidently heeded the commander's prudent orders to be on their best behavior.

The members of the expedition described the Indians they met as affable and it was likely that the villagers viewed the wayfarers as potential trading partners and possible allies against their traditional enemies. However, the genuine hospitality of their village hosts was made abundantly apparent when two of Santiago's apprentice seamen went missing. One of them, Pedro Lorenzo, having returned to his ship, implicated the natives in his disappearance and that of his shipmate Joseph Antonio Rodriguez. Amicable relations could have taken a turn for the worse when Hezeta, much to the disapproval of his fellow officers, conducted his search through the village for the second seaman in a hot-headed rampage. When the truth was found that the Indians had nothing to do with the desertion of Rodriguez, Lorenzo was punished for his inveracity, but in an expression of compassion, the Tsurai residents intervened on his behalf, imploring the commander to spare him the scourging.

During their stay, the officers and chaplains recorded the character and culture of their Tsurai hosts and neighboring Indians in vivid detail. As well, on their forays near the bay, they give an impression of the lushness of the nearby countryside, its mountains, forests, and seashores. Bodega and his second officer, Francisco Antonio Mourelle, produced the first chart of the Port of Trinidad. An excursion was made to a river to the south of the bay by Hezeta and Mourelle for which they named Rio de las Tortolas (River of the Turtledoves) for the good-sized turtledoves they saw upon arriving (today's Little River). There they befriended another group of Indians with whom they traded beads for sardines and visited a nearby rancheria (perhaps the Wiyot whose northern territorial boundary was at the river).

The expedition departed the Port of Trinidad on the morning of June 19th with assurance that the people of Tsurai would keep the cross on the summit. Successful so far in their mission, the convoy sailed farther north, where their next landing near the Quinalt River of today's Washington State would be neither as friendly or fortuitous as the one at Trinidad Bay, when seven of the Sonora's crew were ambushed. Five of them were killed outright as they tried to maneuver their launch to the beach, two others were lost. Bodega opened fire on a canoe of Indians as they pursued the schooner, killing six of their men. Meanwhile, further down the coast and unaware of the Sonora's trouble, a party from the Santiago had landed and performed a hasty possession ceremony.

Heading into increasingly inclement weather and with the ill health of the crews, the officers embraced the realization that, with the ravages of the long ocean voyage, they were now faced with turning back. However, under the dark skies of a stormy night, the two ships became separated and the Sonora, in the face of the advanced season and scarce supplies, carried on toward higher latitudes while the Santiago, with few hands well enough to sail the ship, made it to a point offshore, west of Vancouver Island, before beginning the return journey down the coast.

Hezeta in the Santiago came upon what he determined be a large bay, this was in fact the mouth of the Columbia River (as it was later named by New Englander Robert Gray in 1792). The Santiago continued reconnoitering the coast until it reached the Port of Monterey. Meanwhile, the schooner Sonora ascended to the region of the Alaskan Pan Handle where they first sighted an island with high, snow-capped mountains, most notably Mt. Edgecumbe (as later named by Captain James Cook). Navigating upward along its coast, Bodega entered a bay and landed to take formal possession (Sea Lion Cove on the north end of Kruzof Island). The next day when he and a party went ashore for water and wood they encountered native people, most likely the Sitka of the Tlingit Nation. A confrontation ensued over the taking of water, but was resolved peacefully. The Sonora pushed northward to its farthest northern point estimated at 58° N. Heading south, sailing close to what they believed to be the mainland, the expedition searched for the entrance to a northwest passage, whereby they came upon a large bay and landed to take possession. There they stayed two days to chart the waters (Bucareli Bay on the west side of Prince of Wales Island, Alaska). Once again, Bodega would make another bold attempt northward, notwithstanding the vulnerability of such a tiny vessel in heavy seas, but with the crew so stricken with scurvy, he resolved to to begin the return journey. Continuing southward, Bodega and Mourelle surveyed the coastline, carefully examining every inlet and charting the waters. Encountering a large inlet (Bodega Bay), the Sonora entered it and traveled to what Bodega believed was an abundant river (Tomales Bay) where they were greeted by Indians in tule canoes (probably Coast Miwoks) who traded with them. By October 7th, they sighted Monterey Bay through the fog, certain of their location when they spotted the Santiago and the San Carlos riding at anchor. There they were greeted by Hezeta and Ayala amidst much fanfare. After a period of recuperation at the Presidio of Monterey, and the crews had been nursed back to health by the Franciscan fathers at the nearby mission of San Carlos Borromeo, the Santiago and Sonora sailed in company to San Blas to report the expedition’s findings. They arrived on the 20th of November, 1775.

The expedition departed the Port of Trinidad on the morning of June 19th with assurance that the people of Tsurai would keep the cross on the summit. Successful so far in their mission, the convoy sailed farther north, where their next landing near the Quinalt River of today's Washington State would be neither as friendly or fortuitous as the one at Trinidad Bay, when seven of the Sonora's crew were ambushed. Five of them were killed outright as they tried to maneuver their launch to the beach, two others were lost. Bodega opened fire on a canoe of Indians as they pursued the schooner, killing six of their men. Meanwhile, further down the coast and unaware of the Sonora's trouble, a party from the Santiago had landed and performed a hasty possession ceremony.

Heading into increasingly inclement weather and with the ill health of the crews, the officers embraced the realization that, with the ravages of the long ocean voyage, they were now faced with turning back. However, under the dark skies of a stormy night, the two ships became separated and the Sonora, in the face of the advanced season and scarce supplies, carried on toward higher latitudes while the Santiago, with few hands well enough to sail the ship, made it to a point offshore, west of Vancouver Island, before beginning the return journey down the coast.

Hezeta in the Santiago came upon what he determined be a large bay, this was in fact the mouth of the Columbia River (as it was later named by New Englander Robert Gray in 1792). The Santiago continued reconnoitering the coast until it reached the Port of Monterey. Meanwhile, the schooner Sonora ascended to the region of the Alaskan Pan Handle where they first sighted an island with high, snow-capped mountains, most notably Mt. Edgecumbe (as later named by Captain James Cook). Navigating upward along its coast, Bodega entered a bay and landed to take formal possession (Sea Lion Cove on the north end of Kruzof Island). The next day when he and a party went ashore for water and wood they encountered native people, most likely the Sitka of the Tlingit Nation. A confrontation ensued over the taking of water, but was resolved peacefully. The Sonora pushed northward to its farthest northern point estimated at 58° N. Heading south, sailing close to what they believed to be the mainland, the expedition searched for the entrance to a northwest passage, whereby they came upon a large bay and landed to take possession. There they stayed two days to chart the waters (Bucareli Bay on the west side of Prince of Wales Island, Alaska). Once again, Bodega would make another bold attempt northward, notwithstanding the vulnerability of such a tiny vessel in heavy seas, but with the crew so stricken with scurvy, he resolved to to begin the return journey. Continuing southward, Bodega and Mourelle surveyed the coastline, carefully examining every inlet and charting the waters. Encountering a large inlet (Bodega Bay), the Sonora entered it and traveled to what Bodega believed was an abundant river (Tomales Bay) where they were greeted by Indians in tule canoes (probably Coast Miwoks) who traded with them. By October 7th, they sighted Monterey Bay through the fog, certain of their location when they spotted the Santiago and the San Carlos riding at anchor. There they were greeted by Hezeta and Ayala amidst much fanfare. After a period of recuperation at the Presidio of Monterey, and the crews had been nursed back to health by the Franciscan fathers at the nearby mission of San Carlos Borromeo, the Santiago and Sonora sailed in company to San Blas to report the expedition’s findings. They arrived on the 20th of November, 1775.

Although the voyages of 1774 and 1775 are not as widely known as Captain James Cook's 1776-79 expedition to the North Pacific, they did have an impact on later Enlightenment era investigations. As commandant of San Blas, Bodega himself lead the Expedition of the Limits (1792) in which a number of Spanish voyages convened to explore the waters of the Pacific Northwest and where he also met with English captain George Vancouver for negotiations at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. Trinidad was later visited by Vancouver during his global expedition (1790 - 95), the location of which was known from a translation of Mourelle's 1775 journal. During their brief visit, botanist Archibald Menzies ventured to the summit on the headland where he came upon the cross left by the Hezeta - Bodega expedition 18 years earlier. Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, for whom Humboldt County was named, although he himself had not visited the area, gives accounts of the Pérez expedition and that of Hezeta - Bodega - Ayala which he begins in his Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain, “This voyage, which singularly advanced the discovery of the northwest coast, is known from the journal of the pilot Maurelle [Mourelle],...”

The Hezeta and Bodega expedition stands out for its invaluable notes on local geography, climate, tides, native flora and fauna, as well as its cultural and social observations of indigenous peoples, and it has the distinction of surveying most of the coastal features that gave us, for the first time, a reasonably accurate look at the West Coast of North America.

For a moment in time, the everyday life of the quite village of Tsurai and its neighbors intersected with the international affairs of far reaching colonial empires. It was however, the American Republic which began its own formation that very year that would one day inherit the claim of California and its North Coast as part of the United States. As for the voyage of the Santiago and the Sonora, that expedition would capture for us a remarkable glimpse into what this land and life was like 240 years ago.

-Dina Fernandez

The Hezeta and Bodega expedition stands out for its invaluable notes on local geography, climate, tides, native flora and fauna, as well as its cultural and social observations of indigenous peoples, and it has the distinction of surveying most of the coastal features that gave us, for the first time, a reasonably accurate look at the West Coast of North America.

For a moment in time, the everyday life of the quite village of Tsurai and its neighbors intersected with the international affairs of far reaching colonial empires. It was however, the American Republic which began its own formation that very year that would one day inherit the claim of California and its North Coast as part of the United States. As for the voyage of the Santiago and the Sonora, that expedition would capture for us a remarkable glimpse into what this land and life was like 240 years ago.

-Dina Fernandez