Nellie McGraw and The Hoopa Valley Reservation 1901-1902

Nellie McGraw and the Hoopa Valley Reservation 1901-1902

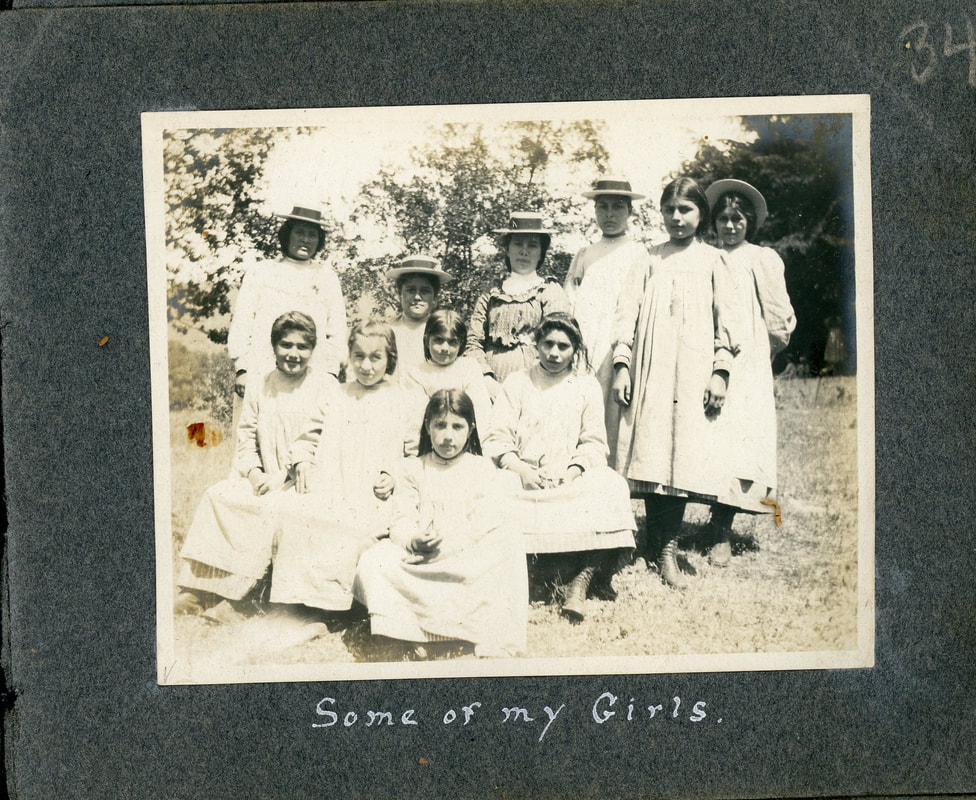

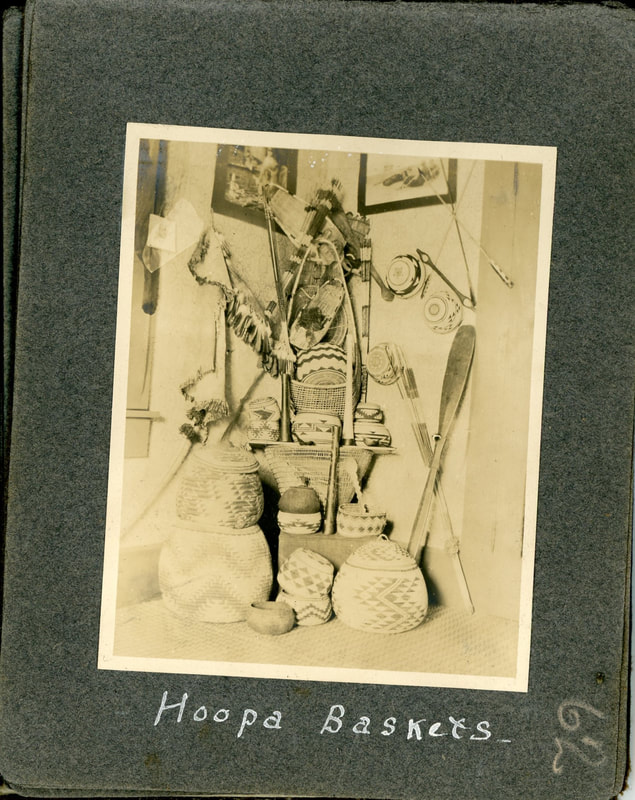

Nellie McGraw was born in the San Francisco area and traveled to the Hoopa Valley Reservation after graduating high school in 1901. As a young woman she made the journey from the Bay Area to the remote Hoopa Valley Reservation where she worked as a teacher at the Presbyterian Church. Nellie McGraw and the Hoopa Valley Reservation explores the personal collection she accumulated during her stay on the reservation.

This exhibit is unique because it offers a different perspective, Nellie McGraw was not documenting her experience for the academic sphere but for her own personal collection, which includes photographs, journal entries, baskets, and a pair of beaded moccasins.

Nellie McGraw was born in the San Francisco area and traveled to the Hoopa Valley Reservation after graduating high school in 1901. As a young woman she made the journey from the Bay Area to the remote Hoopa Valley Reservation where she worked as a teacher at the Presbyterian Church. Nellie McGraw and the Hoopa Valley Reservation explores the personal collection she accumulated during her stay on the reservation.

This exhibit is unique because it offers a different perspective, Nellie McGraw was not documenting her experience for the academic sphere but for her own personal collection, which includes photographs, journal entries, baskets, and a pair of beaded moccasins.

|

An Analysis of Nellie McGraw’s Mission to the Hoopa Reservation

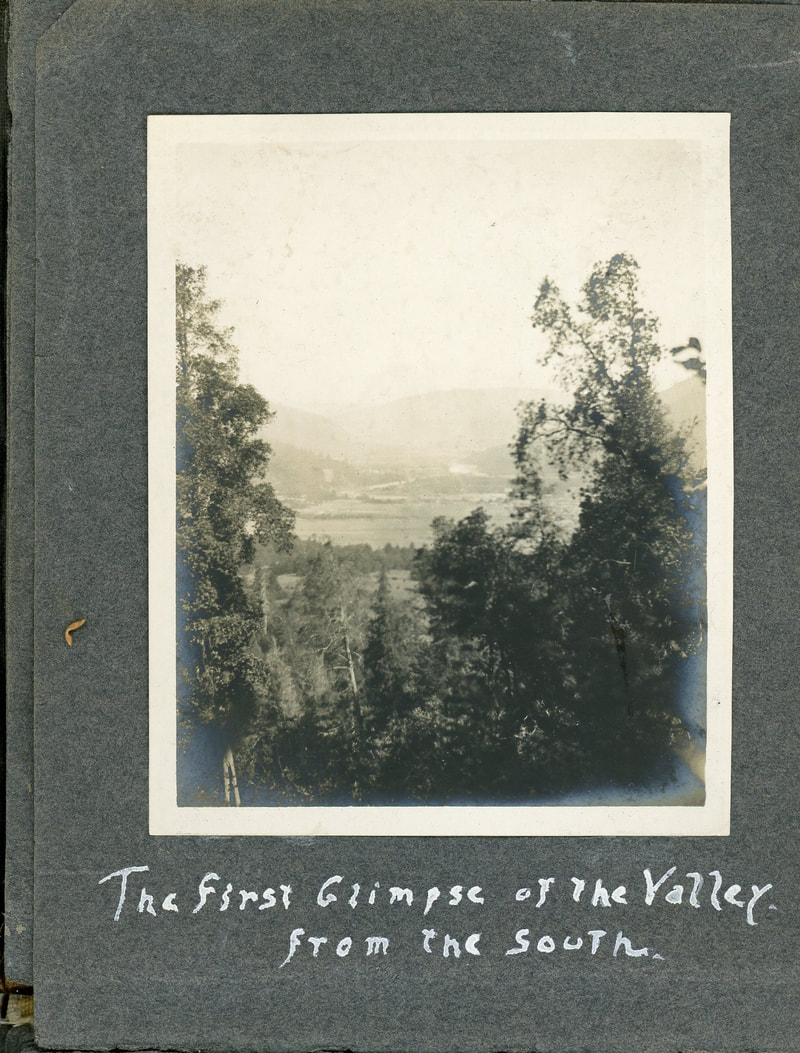

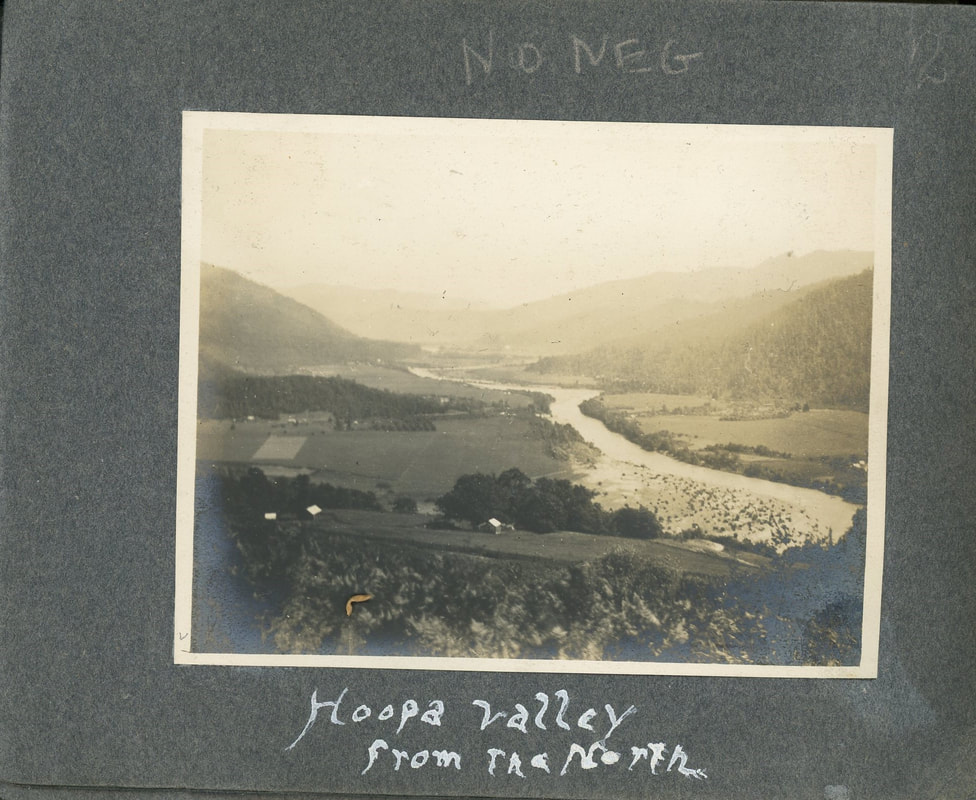

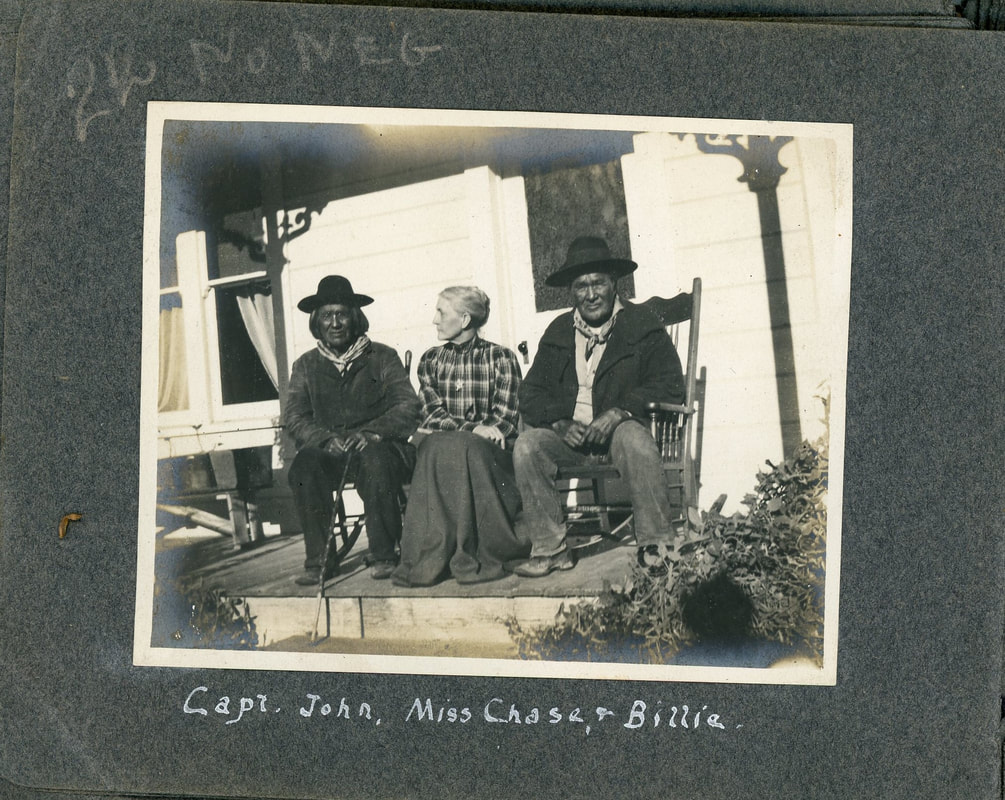

Spanish Missions were established along the California Coast by 1769. Those sites were religious labor camps that exploited Indigenous peoples to benefit the colonizers. Missionaries believed they were helping Indigenous people by forcing them to renounce their traditions and “saving” those considered “savages.” In 1806, thousands of Indigenous children and adults died from measles. Spanish missionaries' practiced separating children from their parents and kept them prisoner in squalor, which contributed to the spread of the fatal disease. Despite these conditions, the Indigenous peoples of California resisted colonizing forces and fought to maintain their land, culture, and sovereignty. Nellie McGraw was born in a mansion in East Bay, California, on 01 October 1874. In 1901, she graduated from high school and left her home in Oakland to pursue missionary work in the Hoopa Valley. This setting change was radical, as McGraw had to travel by way of pack mule trains over trails to the far reaches of Northern California. The largest nearby major settlement of the time was Eureka, CA, home to 7,327 (1900 census record), compared to today’s population of 26,489 (2021 census record). She was sent to work as a teacher with Miss Martha Chase at the Presbyterian Church. Both McGraw and Chase, who joined her, shared the common sentiment of the time that the Hupa people could be convinced to give up their traditions; and that by doing so, they were helping. Upon arrival in Hupa in 1901, both taught Sunday school and encouraged women and girls to learn to make bread, sew clothes, and clean their homes the same way Whites did. Both women were sent to sanitize the Hupa people of their culture. However, they inadvertently aided in strengthening and preserving it. Nellie McGraw photographed life on the Hoopa Valley Reservation and documented daily interactions with others in detail in her journals. Her journals have unfortunately been lost to time but a section of her writing was published in the Blue Lake Advocate in the 1960’s. The information within her journals would be an incredibly valuable resource if they are ever recovered. Chase documented a moment of doubt after the superintendent had disrupted a ceremonial dance (the specific ceremony was not documented), and the Indigenous community came to her home to protest. She took this opportunity to preach about the importance of giving up dance, but they were not swayed. In return, she was met with speeches on the importance of maintaining ceremonial dance. This event shook Chase’s belief in her actions. She wrote, “it is pitiful to rub a religion from a people that can be so sincere and earnest as these are...May we make no mistake." Many individuals likely faced similar experiences while attempting to “civilize” Indigenous communities throughout California. What is interesting here is that we have insight into how this conflict made Miss Chase feel. Her goal was to “civilize” the community by introducing them to Presbyterian religion. However, she clearly acknowledged their established religion, even though it is contrary to her own beliefs. Chase frequently purchased baskets woven by women of the Hoopa Valley Reservation and sold them to private collectors; including Brizard’s, a shop located in nearby Arcata, CA. She passed on special requests from buyers for specific colors or shapes. And even recorded how baskets were made and their many applicable uses. Chase did not realize that basket weaving and spirituality cannot be separated. By encouraging women to weave for profit, she inadvertently helped strengthen and preserve the art of basket weaving. Hupa Women earned income by weaving baskets and subsequently taught their children to weave as both a tradition and a source of income. The prominent evidence of McGraw’s journey to the Hoopa Valley Reservation was captured through her use of a Brownie Camera and her meticulous daily notes written in her journal. Her photographs are unlike others from that time period (1901-1902). Unlike her counterparts, she did not document the Hupa Tribe’s way of life with an eye for art, profit, or research. Instead, she photographed members of the tribe and the landscape for her own personal collection. As a result, her photos are significantly more representative of daily life than the staged photos taken by many researchers or artists of the period. Information provided by “Tales of Subversion: How Native Peoples and Some Whites Sabotaged Federal Efforts to Kill a Culture” Cathleen Cahill, North Coast Journal. “Short Overview of California Indian History,” The State of California Native American Heritage Commission |