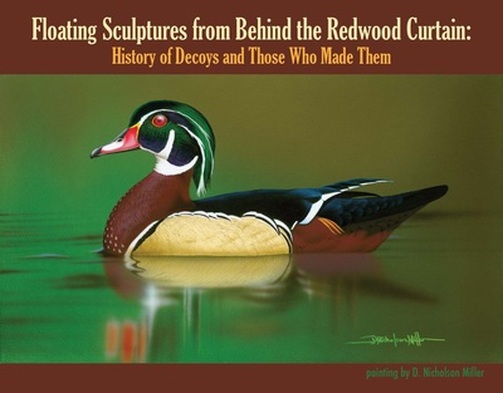

Floating Sculptures from Behind the Redwood Curtain

February 1, 2014 through May 7, 2014

The creation of decoys originated in America with the Native Americans. While local Native American tribes preferred nets for hunting waterfowl, tribes as close as Nevada and as far away as the East Coast utilized decoys to lure their prey since time immemorial. Natives Americans across North America used cattails, bulrush and the tule plant for making floating decoys to lure waterfowl to roosting areas to be bow-hunted, netted, or snared. Geese and other migratory birds, passenger pigeon, cormorant, swan, as well as turkey, grouse and partridge were important game birds to Native Americans. Decoys excavated from the Lovelock Cave in Nevada were found to be nearly 4,000 years old and were made from tule reed, a plant species related to bulrush. Native Americans, in turn, taught the Pilgrims how to create decoys for survival purposes. Decoys were unknown in Europe prior to contact with Native Americans.

In the late nineteenth century, the market gunner appeared on the scene and took the enterprise of wildfowl hunting to a new level. Two men with a double-barreled shotgun could bag six hundred birds in a day, sell them on the market and make a good living doing it. To fill the orders of the many hunters, factory decoys were born, exerting a strong influence in the standardization of decoys. The making of decoys by machinery had its beginning in the years following the Civil War. The new product immediately became known as the factory decoy. Among the earliest of them were the Dodge factory and the Mason factory, both of Detroit, Michigan. Fortunately, the old art of making decoys did survive, for many rural hunters preferred their own decoys to the factory products and some could not afford the purchase price of the “store-bought” decoy. Locally, market hunters George and Wes Dean of Samoa and Frank Deuel, who lived his entire life along the Humboldt Bay, supplied wildfowl to the local market as well as shipping them to San Francisco. While Frank Deuel didn’t bother with decoys, preferring the more efficient method of sculling up on unsuspecting flocks of ducks and Brant, a bad day for him was taking less than 50 birds! A typical season’s bag was about 4000 birds.

By the end of the 20th century it became apparent that wildfowl numbers were dropping significantly and that federal regulations were needed. In 1913, a federal migratory bird act was passed which prohibited all spring shooting, all night shooting and the shipment of birds. In 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which the U.S. entered into with Canada, protected the waterfowl of North America over the entire range of its migratory flight and brought to an end all shorebird gunning; today each state has its own restrictions as to season length, bag limits and shooting hours--and hunting licenses are required. These conservation measures prohibited the sale of wildfowl and outlawed battery shooting. While laws were passed, the Dean brothers were undeterred. As local legend has it, they continued to ship wildfowl to the San Francisco market by hiding them in coffins to avoid detection! None-the-less, the age of market hunters had ended, and with it factory decoys declined in popularity, reviving the old art of decoy carving.

South of the Lake Earl region in the Crescent City area and the lagoons, tidal Humboldt Bay and the wet pastures of the Eel River Bottoms create a wide coastal plain very different from the commonly encountered rain forest, coastal bluffs, and mountains that surround it. Here, we find the most important waterfowl hunting and decoy carving tradition on the North Coast, focused on Black Brant. Arcata, Eureka, Loleta, and other fishing and logging communities surrounding Humboldt Bay produced the most and best carvers, who took advantage of the great abundance of the light, easily worked, and rot-resistant old growth redwood. Humboldt Bay decoys typically have solid or hollowed redwood bodies, are heavily weighted to prevent swamping in high seas, and rarely used glass eyes often opting for a brass tack. The large number of decoy makers whose works are represented here demonstrate that the Humboldt Bay region is rich in decoy making history. These carvers rank as some of the top creators of the decoy art form in the country.

American folk art is the art of the people who sought personal expression in the everyday objects they made primarily for common use. While many of the decoys you’ll see in this exhibit were used for hunting, thankfully many of these older decoys have survived. This includes many of the old factory decoys and contemporary decoys which are meticulously carved and painted.

Thank you to all the carvers and collectors who loaned us decoys for this exhibit: Bill Pinches, Ben Sheppard, Betty and Doug Oliveira, Gerry and Carol Hale, Rick Banko, Jim Brown, Jim Hunter, John Winzler, Robert Chase and Rosemary Hunter.

A special thank you to Pacific Outfitters for sponsoring this exhibit. Without your generosity this exhibit would not have been possible.

The history of waterfowling text above came directly from the following sources: Joel Barber, Wildfowl Decoys, 1934; Adele Earnest, The Art of the Decoy, 1982; Mike Miller and Fred Hanson, Wildfowl Decoys of the Pacific, 1989; Mike Miller, Wildfowl Decoys of California, forthcoming. http://www.nativetech.org/decoy/DUCKDECOYS.htm

The creation of decoys originated in America with the Native Americans. While local Native American tribes preferred nets for hunting waterfowl, tribes as close as Nevada and as far away as the East Coast utilized decoys to lure their prey since time immemorial. Natives Americans across North America used cattails, bulrush and the tule plant for making floating decoys to lure waterfowl to roosting areas to be bow-hunted, netted, or snared. Geese and other migratory birds, passenger pigeon, cormorant, swan, as well as turkey, grouse and partridge were important game birds to Native Americans. Decoys excavated from the Lovelock Cave in Nevada were found to be nearly 4,000 years old and were made from tule reed, a plant species related to bulrush. Native Americans, in turn, taught the Pilgrims how to create decoys for survival purposes. Decoys were unknown in Europe prior to contact with Native Americans.

In the late nineteenth century, the market gunner appeared on the scene and took the enterprise of wildfowl hunting to a new level. Two men with a double-barreled shotgun could bag six hundred birds in a day, sell them on the market and make a good living doing it. To fill the orders of the many hunters, factory decoys were born, exerting a strong influence in the standardization of decoys. The making of decoys by machinery had its beginning in the years following the Civil War. The new product immediately became known as the factory decoy. Among the earliest of them were the Dodge factory and the Mason factory, both of Detroit, Michigan. Fortunately, the old art of making decoys did survive, for many rural hunters preferred their own decoys to the factory products and some could not afford the purchase price of the “store-bought” decoy. Locally, market hunters George and Wes Dean of Samoa and Frank Deuel, who lived his entire life along the Humboldt Bay, supplied wildfowl to the local market as well as shipping them to San Francisco. While Frank Deuel didn’t bother with decoys, preferring the more efficient method of sculling up on unsuspecting flocks of ducks and Brant, a bad day for him was taking less than 50 birds! A typical season’s bag was about 4000 birds.

By the end of the 20th century it became apparent that wildfowl numbers were dropping significantly and that federal regulations were needed. In 1913, a federal migratory bird act was passed which prohibited all spring shooting, all night shooting and the shipment of birds. In 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which the U.S. entered into with Canada, protected the waterfowl of North America over the entire range of its migratory flight and brought to an end all shorebird gunning; today each state has its own restrictions as to season length, bag limits and shooting hours--and hunting licenses are required. These conservation measures prohibited the sale of wildfowl and outlawed battery shooting. While laws were passed, the Dean brothers were undeterred. As local legend has it, they continued to ship wildfowl to the San Francisco market by hiding them in coffins to avoid detection! None-the-less, the age of market hunters had ended, and with it factory decoys declined in popularity, reviving the old art of decoy carving.

South of the Lake Earl region in the Crescent City area and the lagoons, tidal Humboldt Bay and the wet pastures of the Eel River Bottoms create a wide coastal plain very different from the commonly encountered rain forest, coastal bluffs, and mountains that surround it. Here, we find the most important waterfowl hunting and decoy carving tradition on the North Coast, focused on Black Brant. Arcata, Eureka, Loleta, and other fishing and logging communities surrounding Humboldt Bay produced the most and best carvers, who took advantage of the great abundance of the light, easily worked, and rot-resistant old growth redwood. Humboldt Bay decoys typically have solid or hollowed redwood bodies, are heavily weighted to prevent swamping in high seas, and rarely used glass eyes often opting for a brass tack. The large number of decoy makers whose works are represented here demonstrate that the Humboldt Bay region is rich in decoy making history. These carvers rank as some of the top creators of the decoy art form in the country.

American folk art is the art of the people who sought personal expression in the everyday objects they made primarily for common use. While many of the decoys you’ll see in this exhibit were used for hunting, thankfully many of these older decoys have survived. This includes many of the old factory decoys and contemporary decoys which are meticulously carved and painted.

Thank you to all the carvers and collectors who loaned us decoys for this exhibit: Bill Pinches, Ben Sheppard, Betty and Doug Oliveira, Gerry and Carol Hale, Rick Banko, Jim Brown, Jim Hunter, John Winzler, Robert Chase and Rosemary Hunter.

A special thank you to Pacific Outfitters for sponsoring this exhibit. Without your generosity this exhibit would not have been possible.

The history of waterfowling text above came directly from the following sources: Joel Barber, Wildfowl Decoys, 1934; Adele Earnest, The Art of the Decoy, 1982; Mike Miller and Fred Hanson, Wildfowl Decoys of the Pacific, 1989; Mike Miller, Wildfowl Decoys of California, forthcoming. http://www.nativetech.org/decoy/DUCKDECOYS.htm