The Fight to Save the Redwoods

Origins of the Redwood Preservation Movement

|

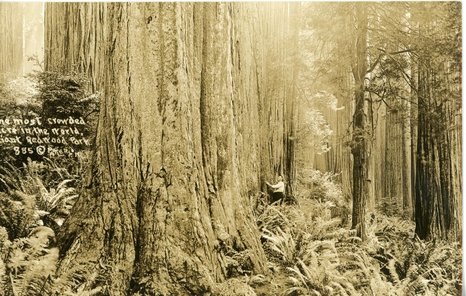

The redwood preservation movement is a lengthy one, traditionally seen to have begun in 1918 with the founding of Save the Redwoods League. However, Redwood preservationist action does reach as far back as 1852, right after the state of California was created. At this point in time, the forests appeared to be endless and there was no popular support for preserving the trees. The earliest organized and successful movements in the early 1900s occurred around the rapidly growing San Francisco Bay area and the Santa Cruz mountains, moving their way up the coastline as the forests were logged. Conservation in the northernmost reaches of California began in earnest with the founding of Save the Redwoods League in 1918, who themselves had benefited from earlier, locally based women’s campaigns to preserve outstanding groves in local parks. Much of the early League work was in preserving the groves around the area now known as the Avenue of the Giants in southern Humboldt County, which later formed into Humboldt Redwoods State Park. From there, the league moved their work northward as they worked to purchase and donate land to what would later become the world famous California State redwood parks of Prairie Creek, Del Norte Coast Redwoods, and Jedediah Smith Redwoods.

|

|

Proposals for a Redwood National Park had been briefly discussed in the 1920s and 1930s as the League chipped away at purchasing privately held groves to donate to the State, however, the topic arose again in 1946, as a proposed National Forest to be named after Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a park that would reach from Sonoma County to the Oregon border and managed under selective cutting practices controlled by the US Forest Service. This sweeping park which would encompass 90% of both Humboldt and Del Norte counties was heavily opposed by locals, Congress, and Save the Redwoods League, which was more focused on adding lands to the State Parks rather than to a Forest Service operated selective cutting system.

|

|

The Forest Service System wasn't blocked from logging on Forest Service land-which would only mean that the redwoods owned by the Forest Service would be logged by the federal government rather than private industry. Following World War 2, logging rates boomed again in response to accelerated construction and more advanced equipment including motorized drag saws. Companies began to move from selective cutting towards clear cutting and thousands of privately held virgin old growth was logged. Conservationists had to act quickly to save what was left.

An Unprecedented Challenge

The challenge when it came to create a Redwood National Park in the 1960s was that the potential park land was owned by private land holders, meaning that the federal government would have to pay heartily to purchase the land for the park, which was unprecedented. All National Parks before had been land already owned by the federal government that was reclassified to be a National Park.

In 1961, federal funds purchased the land that became Cape Cod National Seashore, presumably paving the way for the federal purchase of land that would become Redwood National Park, but there were more hurdles to overcome. Up to this point, Redwood forests that had been incorporated into the State Parks by Save the Redwoods League were purchased by private donations, either by individuals or groups, who would then get to name the grove that their money helped purchase. To make a sizable and meaningful National Park, the federal government would need to be involved because they had the money needed to purchase vast tracts of redwood at one time rather than in stages. Logging in the area was happening so quickly that this tactic of slowly building a park would move too slowly to save larger land parcels. Before this point, Save the Redwoods League generally opposed the National Park Service for several interesting reasons, many having to do with the League's opposition to the development of areas that had become parks. When the speed of logging was showing that proposed parklands could be destroyed in a matter of a few weeks, the League reconsidered.

In 1961, federal funds purchased the land that became Cape Cod National Seashore, presumably paving the way for the federal purchase of land that would become Redwood National Park, but there were more hurdles to overcome. Up to this point, Redwood forests that had been incorporated into the State Parks by Save the Redwoods League were purchased by private donations, either by individuals or groups, who would then get to name the grove that their money helped purchase. To make a sizable and meaningful National Park, the federal government would need to be involved because they had the money needed to purchase vast tracts of redwood at one time rather than in stages. Logging in the area was happening so quickly that this tactic of slowly building a park would move too slowly to save larger land parcels. Before this point, Save the Redwoods League generally opposed the National Park Service for several interesting reasons, many having to do with the League's opposition to the development of areas that had become parks. When the speed of logging was showing that proposed parklands could be destroyed in a matter of a few weeks, the League reconsidered.

The Sierra Club and Save the Redwoods LeagueLeading into the 1960s, the Sierra Club came out as a leader in the movement to establish a park in the Redwood Creek area, while the Save the Redwoods League focused more on establishing a park the Mill Creek area of Del Norte County. In the end, both groups did come together to promote the protection of the redwoods in the National Park largely by raising awareness that one was needed. These groups used a variety of tactics to spread their message, including a tactic that went back to the earliest days of the Redwood preservation movement: pairing powerful photos and emotional writing in newspapers and other publications to promote the cause. This is most clearly seen in internal bulletins and newsletters that were sent out to members, however some campaigns also ran ads in national newspapers to raise awareness.

|

Other activitists like Lucille Vineyard produced documentaries detailing the plight of the redwoods. Coffee table books like “The Last Redwood” also promoted urgency in the movement to save the redwoods. With widespread media campaigns led by the Sierra Club, popular opinion began to favor the establishment of a Redwood National Park. However there were still several road bumps along the way, including the question of purchasing land from private landholders and where the Park would be.

Dueling Locations

When it came to decide where the park should be, there was a rift between Save the Redwoods League and the Sierra Club. Save the Redwoods League had been doing a lot of work acquiring land in the Mill Creek area of Del Norte county. They planned on acquiring the whole watershed, saving old growth in the river flats of the park from uphill logging and erosion, albeit in a relatively small land parcel. The Sierra Club originally preferred a section along the Klamath river, which ended up being logged before any official progress could be made to protect the land. Their second choice was the Redwood Creek area, which could become an expansive 90,000-acre park, encompassing the entire watershed. Government support for the two plans was divided, leading to a longer debate about the location of the park while the redwoods continued to fall. There were claims that certain congressmen who supported certain plans were doing so because they were being paid off by the companies who would be affected. Additional plans were proposed with differences in acreage, location, and cost, but the most well-supported plans focused on Mill Creek or Redwood Creek.

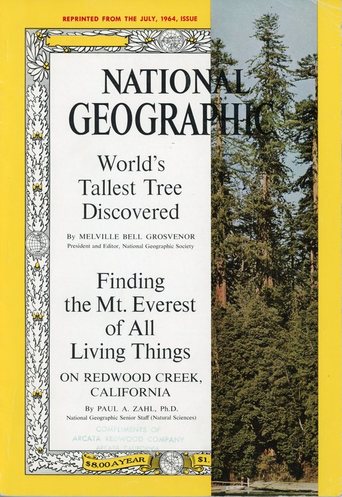

National Geographic Turns the TideIn the end, the National Park Service commissioned a survey done by National Geographic to investigate the Redwood Creek area as a potential National Park site. The site had, in the 1920s, been lauded by one of the founders of Save the Redwoods League as a prime location for a 30,000 to 50,000 acre park. This survey, which was published nationally a few decades after the League founder made his statement, provided a boost to the redwood preservation movement and support for the Redwood Creek site soared -largely due to the fact that the world's tallest known tree had been found over the course of the study.

Congressional hearings took place in 1966 in Crescent City and Washington DC and included hours of testimonies from a number of interested parties from businesses to locals to people from out of the area in support for different park areas and park plans, along with testimonies of dissent from many local businesspeople, unions, and lumber companies. |

Compromise-and the Last Battle

As President Johnson’s term came to a close, a compromise was created to form a 58,000 acre National Park on Redwood Creek that would consist of a combination of State-owned and federally purchased land, however much of the federally purchased land (which made up about half of the new national park) was logged over land that needed extensive rehabilitation. The other half of the land was made up of state parks that would be included within the National Park while maintaining their State Park status, and 20% of the land that was purchased went towards enlarging Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park. The park was officially created on October 2, 1968, however, neither the Sierra Club nor the Save the Redwoods league were satisfied with the results: a strangely shaped park that protected old growth from logging, but not from erosion of uphill logging projects.

The photos above show the Tall Trees area (contained within the bend in the river) and the logging taking place right up to the border of the 1968 park land. Logging within the watershed led to massive erosion that put the river and trees at risk for massive wintertime flooding. Photos taken March 1982 by Don Anthrop.

The Sierra Club and Save the Redwoods league came together to support the expansion plan, with the Save the Redwoods League moving towards supporting government intervention to save the redwoods, rather than a strict focus on individual philanthropy as they had traditionally done with the Memorial Grove program. Within a year, research was being done on how the park was being impacted by logging on the border of the park and it was found that more land had to be acquired to better protect the park land. Termed “ the Last Battle of the Redwood War” by Sierra Club members, the National Park expansion plan was completed in 1978.

Information for this page was found in the following books and provided by the following individuals:

Coast Redwood: A Natural and Cultural History by Michael Barbour et al.

The Fight to Save the Redwoods by Susan R Schrepfer

Don Anthrop

Coast Redwood: A Natural and Cultural History by Michael Barbour et al.

The Fight to Save the Redwoods by Susan R Schrepfer

Don Anthrop